Our K-12 Education practice is always aspiring to enhance our ability to create seamless indoor and outdoor environments that inspire wonder, joy, and insight through inquiry and agency. We are constantly investigating ways to better foster the health and well-being of students, families, and their communities. That’s why our research team jumped at the chance to collaborate with the innovative UCLA Lab School, which has been at the forefront of progressive education since 1882.

The buildings on its current campus were designed in phases by Robert Alexander and Richard Neutra during the 1950s. Lab School Principal Corrine A. Seeds, known as a pioneer of progressive education, had asked them to design an elementary school campus with strong connections to nature and flexible learning environments.

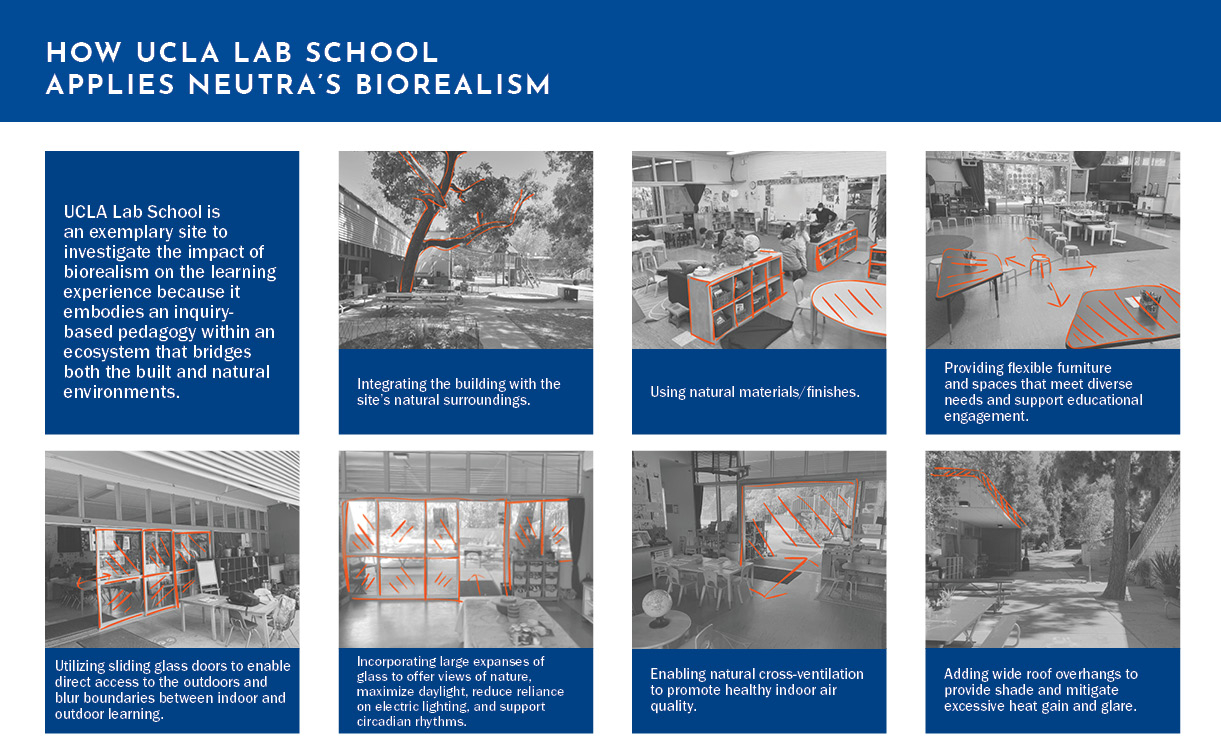

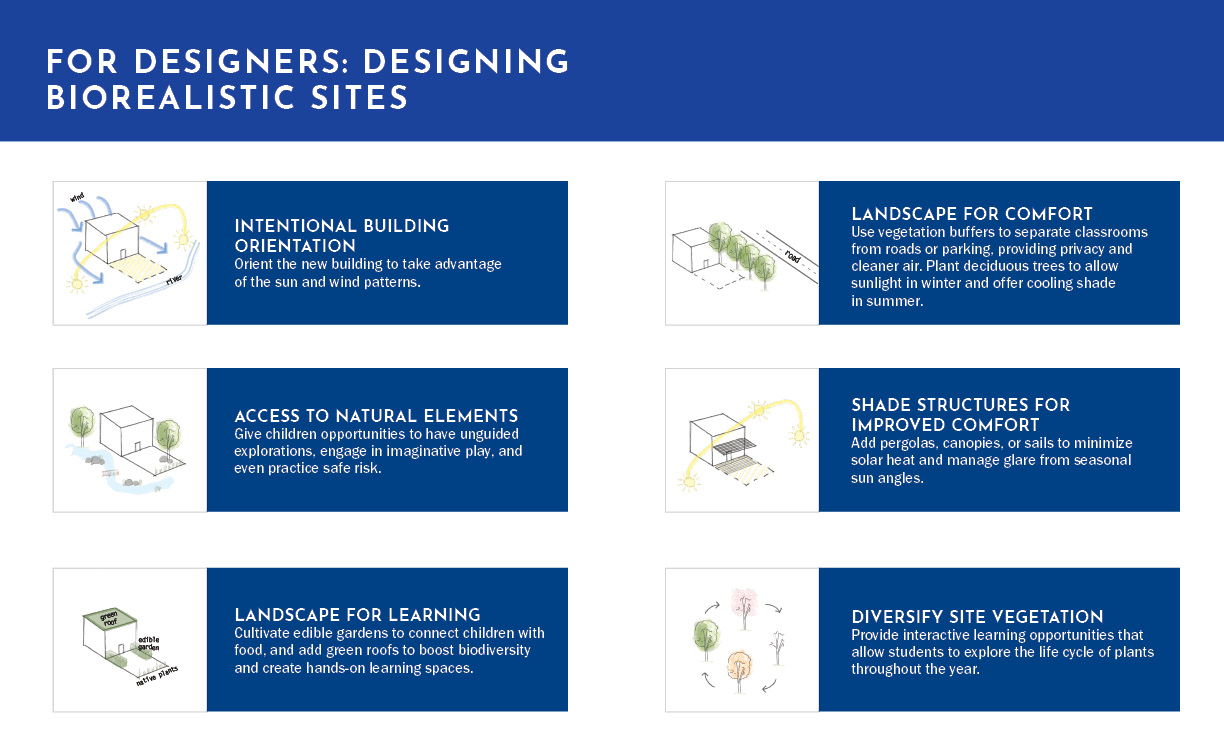

The school is nestled into a bucolic setting, straddling a ravine with a stream running through it, where the building’s architecture reaches out to embrace its environment. The design personifies Neutra’s philosophy of biorealism, which he first described in his seminal book, Survival Through Design, as “the inherent and inseparable relationship between man and nature.”

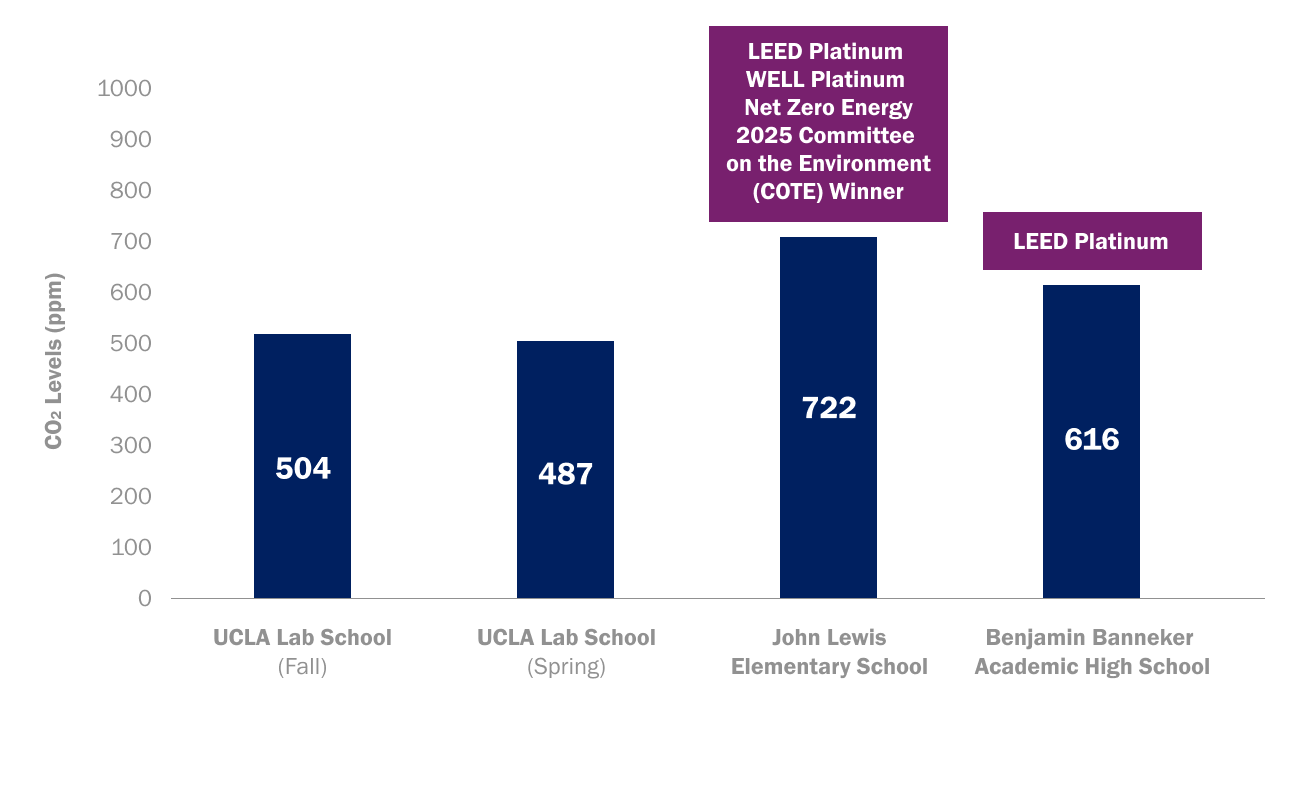

While the school continues to advance our understanding of how children learn, the environmental changes wrought by our warming climate are posing challenges to Neutra’s vision for a learning “landscape” that makes Lab School so special.

Working closely with our research partners at UCLA and Lab School’s teachers and students, we set out to find a way to sustain Neutra’s vision into the future, while providing new insights to help other schools weather these same changes and thrive.