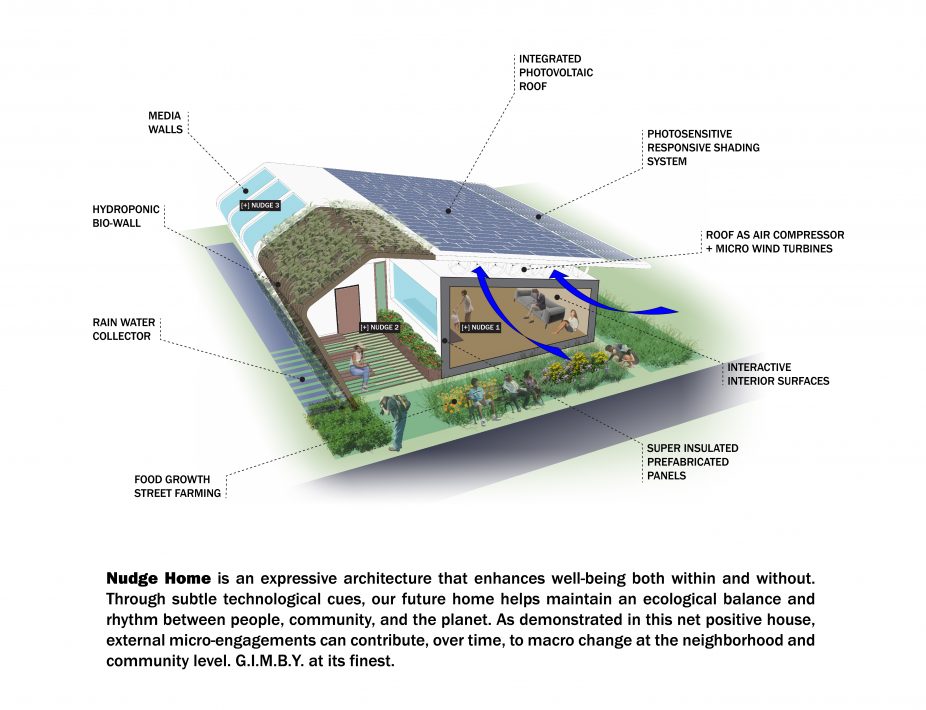

Fast Company magazine profiled Perkins Eastman’s Nudge Home, its vision of the home of the future.

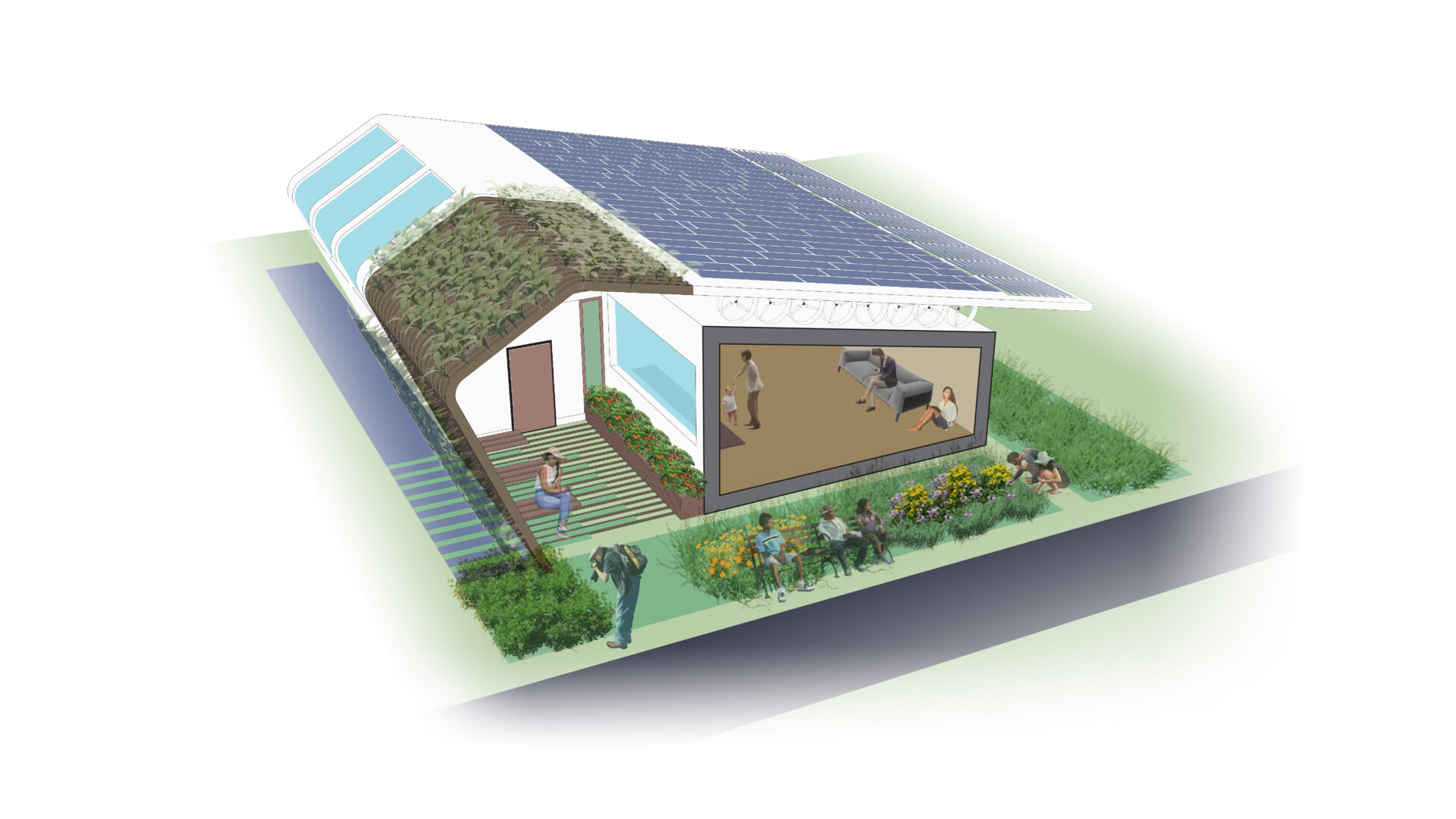

Rendering by Pablo Cabrera Jauregui.

By avoiding the kind of interruptive notifications we get on our devices—Time for your meeting! Time for the gym!—and incorporating subtle technology to “nudge” us into healthier living, Perkins Eastman’s home of the future was highlighted in Fast Company recently. The Perkins Eastman Nudge Home concept was the result of a creative sprint between Co-CEO Nick Leahy, Diaa Hassan and Pablo Cabrera Jauregui, and Communications Associate Melissa Nosal. “I was nervous that we weren’t going to get the concept to Fast Co. in enough time to make it to the finish line,” Nosal said.

The subject line seemed innocent enough when the email popped into Nosal’s inbox on a Friday afternoon. “Hello from Fast Company—Home Concept?” it said. What followed, however, was a challenge to return a fully-formed, future-home concept—with renderings to back it up—within two weeks. Despite the tight turnaround, Leahy said, “We were intrigued. We thought it would be a fun exercise.” Hassan is a facile thinker and would be quick to get the ideas flowing, he explained, while Cabrera Jauregui, with a specialty in computational design, could execute the vision.

The assignment was to devise a home—“the bolder the better”—with design and technology that would be feasible in the next five to ten years. Leahy started the process by invoking the architect Cedric Price, who famously said in 1966: “Technology is the answer, but what was the question?” The team would have to come up with the right questions before dreaming about a future design that could answer them. Three queries emerged: What to do about working at home for hours on end without a break? How do you get your kids off their screens? And the age-old quandary: What’s for dinner?

Hassan started with a basic Google search: What’s the home of the future? “Everything that shows up is very similar. It’s a whole bunch of notifications—on your phone, on your fridge—in a very overt and obvious way. When you’re being overwhelmed like that, you just want to turn it off. [Your home] isn’t just this big phone. I don’t want to live in a house like that,” he said. Instead, he reasoned, “What can we do so it’s centered on the user of the house and not just the capabilities of the house?” Hassan looked outside of architecture for some answers, and remembered a book he’d read called Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein. Based on behavioral economics, the book argues that we’re not always going to make choices that are inherently beneficial to our health or well-being. There needs to be a “nudge” to push us in the right direction. Why, then, can’t we use technology in the home as a nudge rather than a nag? Using that premise as a lens, Hassan revisited the team’s original questions about life in the modern home.