Physical distancing is difficult for a reason; over many thousands of years, humans have evolved to rely on social networks for practical and emotional needs. Through biological and chosen families we create an expansive network of connections that makes us feel wanted and keeps us safe. But the global pandemic has forced us to dismantle these essential networks to ensure our survival. This creates a unique dilemma:

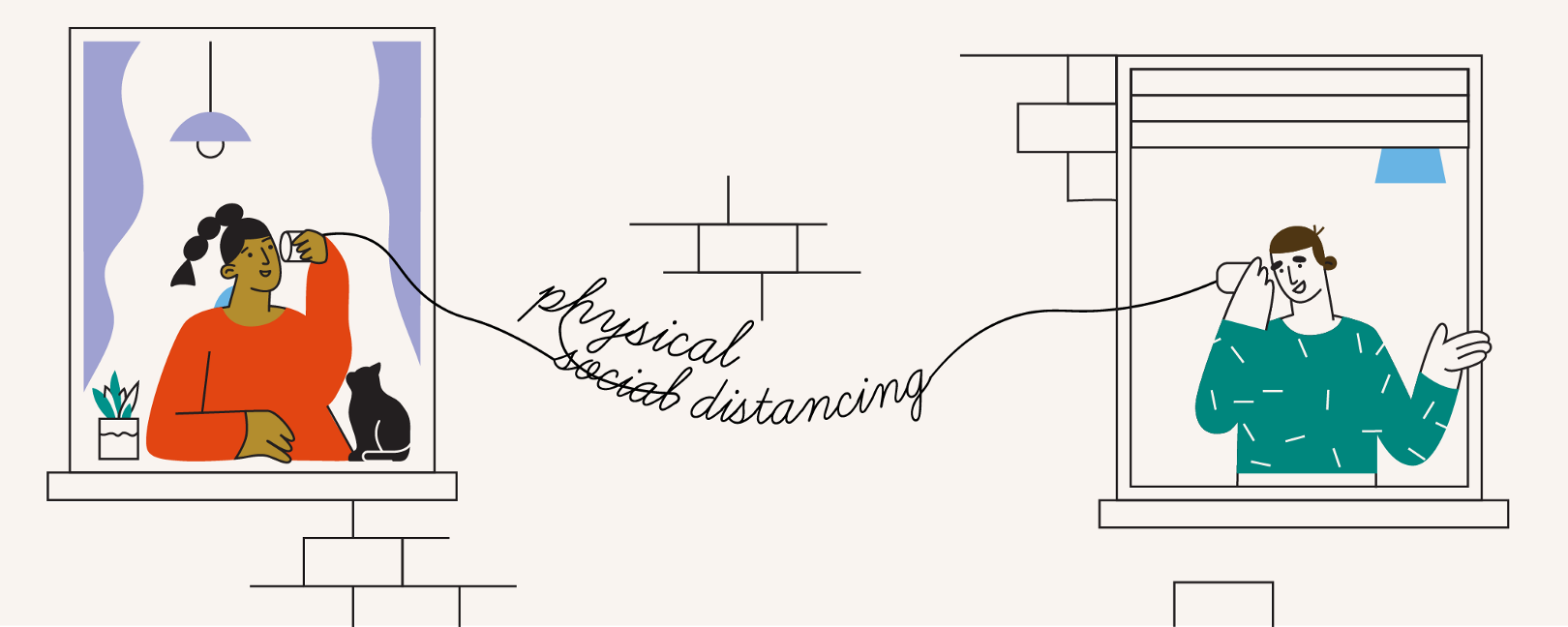

How can we foster the human connections that are so vital to our well-being while maintaining physical distance?

Further confusing the issue, the term we use to define our need to isolate—social distancing—falsely implies that COVID-19 has robbed us of our social connections. In fact, we still have the tools to connect, whether physically distant or not. We have an expansive virtual network at our disposal that allows us to feel connected to our biological and chosen families—to our communities.

Even with access to this virtual network, there remains a tug-of-war between distance and connection that raises important questions for the built environment. As architects, we design spaces that maximize physical human interactions: offices encourage collaboration; parks and plazas invite gathering; schools and campuses maximize activity. We “activate” and “energize” these spaces to encourage community. As the pandemic continues, however, it’s clear the coronavirus will have a lasting impact on the ways we think about space. Distancing, whether by mandate or preference, will likely continue into the foreseeable future.

Going forward, designers will have to balance the need for human connection with the necessity of physical distance. As we adapt to this new reality, what does designing within these parameters look like?

“In architecture, one of the primary things you learn is to look and see, to notice and carefully analyze what you see and what you sense. Now is the time to really reflect on resiliency, desirability, and accessibility. We’ll be considering the options of spatial experiences,” Principal Peter Cavaluzzi, who led the winning competition team for the innovative Port Authority Bus Terminal project in New York. “Both the city and suburbs can offer useful, beneficial lifestyles; technology has allowed both of them to thrive. It’s different than 30 years ago, when we didn’t have all of the communication, transportation, and delivery choices that we do now. Cities need to compete and stay relevant by designing amazing urban places and buildings that make city life so desirable. This will continue to attract people and provide the flexibility and adaptability that creates safety.”